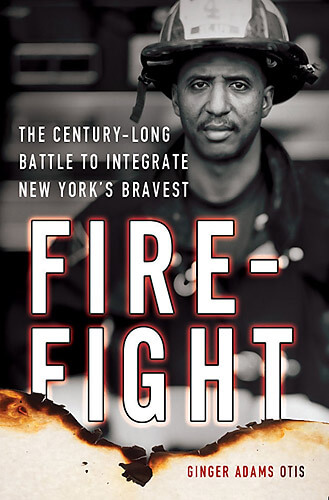

“Firefight: The Century-Long Battle to Integrate New York ’s Bravest” by Ginger Adams Otis

c.2015, Palgrave Macmillan

$28.00 / $32.50 Canada

281 pages

Chestnuts roasting on an open fire seem so cozy.

Just humming that tune warms you up, right? Roaring flames on hearth or sand always seem welcoming, even romantic — except when they go out of control. And as for the person who puts out a fire like that, as you’ll see in “Firefight” by Ginger Adams Otis, flames aren’t all they battle.

Sometimes, the fight runs deeper, as Wesley Williams learned on Jan. 10, 1919.

That was the day Williams left his young family in their Bronx apartment to report to his new job as New York City ’s first (according to newspapers) black firefighter. It was a 45-minute ride to Little Italy, and he knew he could never be late.

What he faced that day, and for months, wasn’t what he hoped to get from the job. He’d receive a $1,500-a-year salary and benefits of which few black men would dare to dream. He also received discrimination, subtly and overtly, but Williams persevered and thrived: in later years, he worked his way up to battalion chief.

That was no easy feat for an African American man in early-to-mid 1900s America .

Though black citizens represented a good part of New York City’s population, black “smoke eaters” were few in both police and fire departments; often, just three percent of the entire department. Early-on, they had little security or clout, which is why Williams formed the Vulcans, a fraternal order for African American firefighters, in 1938. Still, Jim Crow hazing, testing biases, and lack of urgency in City Hall kept many potential African American recruits from the FDNY.

Some 80 years after Wesley Williams became a firefighter, the situation was different, but similar: racism lurked quietly in pockets of the FDNY, testing continued to be a thorny issue, and there was still a disparity in numbers for “Bravest” African Americans. The Vulcans had long lobbied for change, with limited success and so, post-9/11, they took a drastic and controversial step…

In a way, I saw “Firefight” as two distinct books in one.

First, readers may be shocked to learn of the racial imbalance perpetuated in such a large and esteemed department in one of our largest cities, and what had to be done to set things right. That account of modern-day struggles is how author Ginger Adams Otis kicks her book off, and though she winds recent happenings nicely around that of the past, the many names and legal skirmishes can become overwhelming for readers outside New York .

Fortunately, the history of New York firefighting and the decades-old story of Wesley Williams comprise the other half of this book, and the latter is compelling. It weaves through Otis’ account of the present and tempers it; indeed, if your mind wanders, it’ll snap back when Williams’ name appears again.

Fire buffs in particular will appreciate this book, as will anyone who loves a peek into the past with a dash of excitement. Yes, part of it may be a challenge to follow but the other half of “Firefight” will inflame you.