Caribbean justices Sylvia G. Ash and Ruth Shillingford were the keynote speakers at a Continuing Legal Education Program sponsored by the Brooklyn Bar Association and the Judicial Friends Association on Feb. 7.

Justice Ash, who was born in Trinidad and Tobago to Vincentian and Grenadian parents, told Caribbean Life that she and Justice Shillingford, a native of Dominica, spoke on “Issues Arising in Jury Selection and Deliberation in Criminal and Civil Court.”

Justice Ash is the Presiding Justice of the Commercial Division in Kings County Supreme Court.

Justice Shillingford is the president of the Judicial Friends Association and an acting supreme court judge in Kings County Criminal Court.

Justice Ash said they both spoke on the challenges of selecting a jury and issues that may arise during jury deliberations.

She said the packed audience comprised practicing attorneys from both the civil and criminal Bar.

Justice Ash said “this was a very important topic given the fact that Kings County has the largest jury system in New York State and in the entire United States.

“In New York State, once served, it is mandatory that you report for jury duty and that there are no exceptions or waivers,” she said, stating that, each year, over 1 million jury questionnaires are mailed out to potential jurors who are residents of Kings County.

In 2018, Kings County Supreme Court alone conducted about 1,000 Civil jury trials, Justice Ash said.

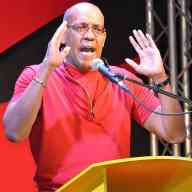

Before starting the lecture, Brooklyn Bar Association President David Chidekel gave a nod to the importance of judicial independence, according to the Brooklyn Daily Eagle.

“Judges without their independence cannot do their jobs equitably and fairly,” Chidekel said. “And I want to thank these two particular judges who have lately stood up and exercised their independence for the benefit of all the citizens of Brooklyn.”

The Daily Eagle said Justice Shillingford began by explaining how she carries out her voir dire process and how it differs from the civil proceeding.

In criminal court, the judge is involved through the entire voir dire process, the Eagle said.

According to Law.com, voir dire originates from

from French, meaning literally “to see to speak.”

The process involves the questioning of prospective jurors by a judge and attorneys in court.

Law.com said voir dire is used to determine if any juror is biased and/or cannot deal with the issues fairly, or if there is cause not to allow a juror to serve (knowledge of the facts; acquaintanceship with parties, witnesses or attorneys; occupation which might lead to bias; prejudice against the death penalty; or previous experiences such as having been sued in a similar case).

After the preliminary screening with the attorneys, Justice Shillingford, according to the Eagle, typically puts 26 potential jurors in the box, uses a questionnaire, gives the attorneys the opportunity to inquire and then allows challenges for cause.

“So, we are all in, in terms of the judge’s role in that process,” the Eagle quoted her as saying.

On the civil side, the judge typically remains available in their chambers during selection, Justice Ash said, according to the Eagle.

“I’ve been a judge for 14 or 15 years, and I have never sat during the selection of a jury,” she said. “In civil court, when a jury comes to you, they’re already ready to be sworn in.”

The Eagle said one example of Justice Ash getting involved in the selection was when a woman whose mother had been in a car accident was being questioned to serve in a motor vehicle accident case.

“It was then Justice Ash’s job to determine if the potential juror could be impartial,” the Eagle said.

In speaking on parts of the process, such as challenges for cause, the use of alternate jurors and deliberations, it said the judges brought in examples from past cases or situations in the courtroom.

For example, on the issue of a juror saying they think they can be fair, Justice Shillingford shared her message, according to the Eagle.

“I’ll say to the juror, pretend you’re on the plane, headed to Bali. The pilot gets on and says, ‘Welcome, I’m looking forward to taking you to Bali,’ and the pilot says, ‘I think I can fly this plane.’ Do you get off the plane or not?” she said, to laughter.

Speaking about social media’s role in the process, the Eagle said Justice Ash gave an example of a juror who shared on her Facebook page that she was serving on a jury, which attracted multiple comments that she did not answer.

The Appellate Division eventually ruled that it wasn’t sufficient to set aside the jury’s verdict in that case, the Eagle said.

Regarding deliberations, it said Justice Shillingford discussed a case in which a deliberating juror “sent a note commenting that the prosecutor was cute, and maybe they would get her number after the trail.”

“The defense claimed the juror was unqualified to serve because they had an eccentric personality,” the Eagle said. “The appellate ruling said ‘eccentrics are not barred from serving on juries.’”

Justice Ash said The Judicial Friends Association was established in 1976 by African-American judges to monitor administrative and policy issues affecting employees of color within the court system, as well as to mentor new judges, attorneys and non-judicial court staff.