Five years ago, the Haitian and the folkloric dance community mourned the death of an icon from their midst, Jean-Léon Destiné. As a dancer and choreographer, he brought Haiti’s traditional music and dance onto American stages and international venues. Soon after his death, dancers influenced by this master, talked of having a major tribute to him.

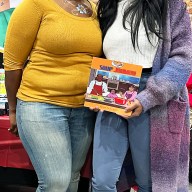

A stellar assembly of dancers and scholars of Destiné formed a committee this past summer, spearheaded by Valerie Rochon, to plan the celebratory Memories of Destiné: A Centennial Celebration that took place on March 29, 2018 to honor him on what would have been his 100th birthday (March 26).

New York Public Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center hosted this homage to this man who danced well into his senior years and influenced hundreds of dancers.

After pouring libations, the evening began with a drum salute from traditional Haitian community drummers — Jean-Guy (FanFan) Rene on Manman Drum, Jean Mary Brignol and Marcus Schwartz on Segon drum and Jude (Yatande) Sanon on Boula Drum.

Archival footage from the Library’s Jerome Robbins Dance Division took former students and colleagues far back in time. What a delight for the audience to watch the 33-year-old Destiné dance in the 1951 film version of Witch Doctor — a dance work inspired by an exorcism ritual.

A film clip of his Harvest Festival Dance from 1954 was also shown.

Jacob’s Pillow Archivist Norton Owen spoke of how Destiné came into his own in the years he spent at Jacobs Pillow — a professional connection as performer and teacher that spanned more than 50 years. Soon after his first Pillow appearance in 1949, Destiné hosted Ted Shawn’s inaugural and impactful two-week excursion to Haiti.

A panel of scholars and dancers shared a litany of personal memories.

The KaNu Dance Theater troupe performed its dance, Breaking the Chains, choreographed by Jessica St. Vil with vocals sung by Riva Nyri Precil and accompanied by the Haitian musicians.

Inspired by Destiné’s dance for agriculture and in honor of the vodou god “Cousin Zaca,” Jean-Aurel Maurice performed Dance Zaca.

Jean-Léon Destiné’s youngest son, Carlo, whose striking resemblance definitely made the audience feel that Destiné was in the house, sang, as is his forte, a medley of Haitian creole songs: Ti moute tetu (Little Tetu), Shango, and L’artibonite. Carlo joined his father’s dance company as a singer from 1970-1980.

“Destiné was my mentor as an adult dancer,” recalls Nadia Dieudonne on this master’s impact, (as many others in the audience). Dieudonne started at first with his company. “I then became his legs for master classes at Jacobs Pillow and in California.” Nadia Dieudonne choreographed the Nago section of “Breaking the Chains”.

She also reconstructed and danced Destiné’s “Ceremony of Rada”— in which the ancestral spirits are called to ensure the continued powers of the religion. Rada is the first rite to open a vodou ceremony.

“It was humbling and symbolic to work alongside original members of his company,” she said, referring to Carolyn Webb, Pat Hall and Jacques Barbot who with others danced the concluding homage of the evening.