While most of us would consider ourselves blessed to possess even one artistic talent, there are those rare individuals who are endowed with such a rich and varied array of talents, it’s mind-boggling.

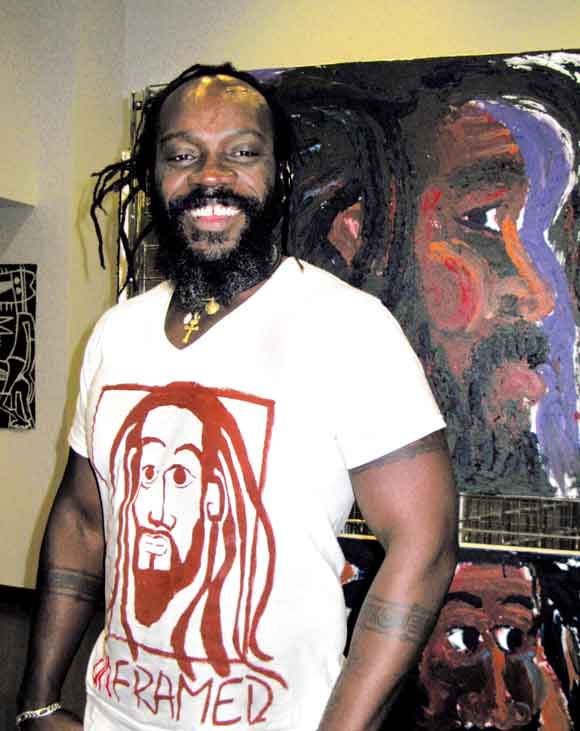

One such person is Iyaba Ibo Mandingo. This remarkable poet, performer, painter, playwright and budding actor brings these talents to the stage in his one-man autobiographical play “unFRAMED: A Man in Progress.” It was performed most recently at the Gerald W. Lynch Theater at John Jay College in Manhattan as part of its 2011 Art of Justice Series, in conjunction with Double Play Connections and Doing Life Productions.

“unFRAMED” can be seen next at the All for One Theater Festival on Nov. 17 and 20.

Basically, “unFRAMED” is the life story of Iyaba Ibo Mandingo – formerly Kenny Athel George DeCruise – who spent his early youth in his native Antigua, and, at age 11, was brought to the United States by his single mother. Like many others who came to this country looking for a better life for themselves and their children, the family overstayed their visas, thus joining the ranks of the undocumented.

Iyaba had to grope his way to manhood in this unfamiliar country without the support and guidance of a father, finding his way in a society in which racism is so entrenched it even instills injustice towards each other in people of color. Eventually he found his niche as a visual artist and a performance poet and writer.

It was Iyaba’s political poetry that almost got him deported. In 2001, shortly after the World Trade Center attack, he delivered a poem that included criticism of the United States foreign policy in relation to the cause of 9/11. Just three days after this performance, he was arrested by Homeland Security and scheduled for deportation.

Seeing a person trying to be honest about himself and his life is always riveting, but to see someone who is immensely talented do so is beyond amazing. During every performance, as Iyaba shares his joys, rage and struggles to redefine his humanity and accept himself, he weaves together prose and poetry, nuanced verbal inflection and eloquent body movement. I guarantee you won’t soon forget the visual image of Iyaba crossing the stage in what can be called an exuberant African stroll, proud and feisty, locked hair flying, or the heartrending image of him becoming the physical embodiment of a grieving tree from which a lynched Black man is hanging. He charms us with delightful stories of growing up under the watchful eye of his loving but tough grandmamma in Antigua, then brings us to tears with his vivid descriptions of the plight of enslaved Africans and modern day immigrants. All the while, on a large white canvas, using his hands instead of paintbrushes, he creates from scratch an original self-portrait!

“unFRAMED” is directed by Brent Buell, himself an accomplished actor and playwright. For ten years Buell volunteered with the non-profit organization Rehabilitation Through the Arts, directing theater in New York State’s maximum-security prisons. The play’s creative consultant and executive producer is Jane Dubin, the TONY Award winning producer and president of Double Play Connections, a company committed to supporting emerging artists and playwrights in the creation and development of new works.

Like the “man in progress” this play is about, the performance, too, has been a work in process. Iyaba, Buell and Dubin, are yet to say, “This is good enough” and call it a day. From its inception onward, they have courageously brought the play before diverse audiences throughout the tri-state area, garnering enthusiastic responses and valuable feedback that has helped the play evolve into its present form.

In an autobiographical presentation, one of the difficult things for any person of color in a white dominant society, and most decidedly for a person who has suffered from racism as both a Black man and an immigrant, is to figure out how to present one’s anger truthfully, neither soft-pedaling it nor turning the whole performance into a diatribe against white people and society.

For me, one of the most powerful things in the play is Iyaba’s reaction to the murder of the East African immigrant, Amadou Diallo, in a hail of 41 police bullets. Iyaba’s fury knows no bounds, and, as the father of three Black sons – his “three Amadous” – he is terrified. As he does in two other places in the play, Iyaba has a debate with his younger self, Kenny, this time about what is the solution to the hatred and how to end the killing. Tormented, Iyaba stalks over to the canvas and gives form to his rage, slamming and splattering the paint onto the canvas with his bare hands. His back to the audience, we hear the sounds of his stifled sobs until the act of painting becomes more gentle. Gradually, it calms him down, and he goes back to telling his story.

When I had the opportunity to speak with Iyaba briefly about what this play means to him, he said, in a word, “Everything.” He went on to tell me that an old family friend from Antigua who saw the play said he was proud of Iyaba for finally doing something with this talent that’s been in his family for generations. Iyaba’s grandfather was once an enormous hit in a play but became a tailor instead, in order to support his family. Iyaba’s mother was forced to abandon her dream of becoming an opera singer when she gave birth to Iyaba at age 19. “So I feel like I’m doing this for my grandfather, grandmother and my mother,” Iyaba explained. “Just to see people appreciate and gravitate towards my work is great. Sometimes I have to sit back and kind of pinch myself.”

Iyaba also said that the satisfaction he got knowing his mother was in the audience watching him pretend at moments to be her was as big as any awards he’s ever gotten (and he’s gotten many). “And as a father of five kids, I’m glad to be able to break that cycle: people of color can feel it doesn’t make any sense to pursue a talent because it’s not practical,” he concluded. “Now my kids are watching me be successful at something I love to do, and I’m pleased as punch.”

Photos by Donna Lamb