Right on the heels of our recently addressing here the dangers thrown up by unchecked fundamentalist behavior, comes a display in Pakistan of exactly how unglued things can become in that kind of highly charged environment. The assassination of the governor of Punjab province by a member of his security detail, apparently because of his outspoken views against the country’s strict blasphemy laws, dramatized the difficulty of achieving any measure of violence-free co-existence where competing factions — in this case secular and religious — vie for domination of the space.

Unpleasant enough under any circumstances, an assassination that goes down in the particular manner of this one adds layers of concern about how good a shot does the society have at political stability, both in the near term and down the road. Tangentially, such an occurrence cannot but recall notable historical precedents in that part of the world within fairly recent memory, Indira Gandhi in India and Anwar Sadat in Egypt having also been taken out by assassins from within their own camps.

Even so, there are elements to the Pakistani incident that seem to place it well beyond the category of isolated eruption from a perhaps hyper-radicalized individual. That the policeman from the elite unit guarding Governor Salman Taseer was able to squeeze off reportedly more than twenty rounds into the body of the governor without drawing fire from any others in the unit, is just one of a number of quizzical details surrounding the killing that engender uneasiness about prospects for a state of normalcy in Pakistan.

Not surprisingly, religious leaders on the right who had been affronted by Taseer’s longstanding campaign against the severity of the blasphemy laws hailed the young man who was the perpetrator. But newspaper reports also told of moderate clerics refusing to condemn the shooting. And even anonymous members of the security forces were quoted as according tacit approval to the assassin’s deed, in effect mimicking the crowds gathered at the suspect’s court appearance, who came out in a show of solidarity.

On the other hand, the turnout of folks, obviously of a whole different stripe, was said to be likewise huge and emotional at Taseer’s funeral, presumably including many who identify with the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), now led by the country’s president, Asif Ali Zardari, widower of slain Benazir Bhutto. Zardari’s precarious position, he being widely perceived as ascending to the presidency solely on account of the wave of sympathy following Bhutto’s assassination, casts him as hardly the tower of strength required of a leadership figure, given the country’s awesome social challenges. Added to which the dark clouds over some of Zardari’s alleged financial finagling back when his wife served as prime minister never have gone away.

Although formally invested with the accoutrements of constitutional democracy, Pakistan has had three periods of rule by so-called “military presidents” since the country was granted independence in 1947. The current political landscape – with Zardari seen as not the strongest of leaders and the PPP in a fragile governing coalition – seems as ripe for shaking as anytime in the country’s turbulent past when military strongmen have thought to assume control. Certainly, prevailing sentiment appears to be that in the present configuration, the head of the military is a more powerful figure than anyone either occupying or aspiring to political office.

All of which suggests that America’s looking in Pakistan’s direction, in this age of al Qaeda and the Taliban, to help shore up its defenses in the battle against terrorism, is fraught with risk. Episodes like the recent assassination serve as graphic reminders of how deeply ingrained is hard-line Islamist sentiment in the fabric of Pakistani society. It should not be thought peculiar that, almost 10 years after its onset, the war in Afghanistan looks to be as unwinnable as it ever was, Pakistan as America’s ally clearly not having delivered so far, as conduit or buffer, at whatever has been America’s level of expectation.

Even absent those international ramifications, though, there’s obviously a combustibility about Pakistan’s insular factions that couldn’t but exacerbate the responsibilities of governance. One wonders whether even Benazir Bhutto, with as loyal a following as was evidently drawn to her, could have successfully overridden the challenges posed by such rugged terrain. In those circumstances the specter of the military again asserting its will looms large. And maybe a claim from that quarter that therein lies the country’s only viable leadership option would be advanced without fear of contradiction. It bears remembering that the three interludes of military presidencies in the country haven’t exactly been brief stop-gap measures; altogether they amassed more than 30 years.

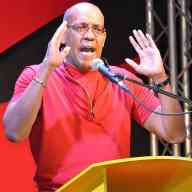

But then there’s this. In reporting on the assassination and the traditional battle lines formed by religious hard-liners and progressive elements, the New York Times included the observation of an author and journalist, Ahmed Rashid, who was described as an expert on the Taliban and radical Islamism. “We have a small minority of extremists,” he said, “and a small number of liberals speaking out, but the very large silent majority are people who are not extremist in any way, but they are not speaking out.”

In the midst of a decidedly troubling outlook for non-devotees of religious extremism, this man’s theory of a non-extremist silent majority, if correct, might be just about all there is by way of hope.