PORT-AU-PRINCE, Nov. 10, 2010 – All across Haiti, United Nations, bilateral and non-governmental agencies are running scores of “cash-for-work” programs. But are they working?

The humanitarian agencies that run the $5-a-day job programs [see Sidebar 1] claim they helped “relaunch” the economy and now are supporting “reconstruction and disaster risk reduction, increas[ing] the sustainability of agricultural rehabilitation and stimulat[ing] the local economy,” to quote the World Food Program (WFP).

“The idea is to increase the amount of agricultural land in the countryside so that people can earn more from their land,” Stephanie Tremblay, WFP communications officer, told Haiti Grassroots Watch.

And where people are clearing roads or rubble or building canals, there are tangible effects, although some are temporary [see Sidebar 2]. But other effects are more lasting. The jobs programs – employing somewhere between 5,000 and 50,000 people a day, although nobody seems to know for sure – do much more than inject cash into the economy.

Not unexpectedly, this kind of deal engenders some corruption and favoritism, as local “strong men” or political leaders pass out jobs in exchange for kickbacks or votes. But these kinds of concerns are minor compared with other consequences.

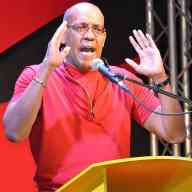

“The main impact of cash-for-work is on the circulation of money,” noted Haitian economist Gerald Chéry, adding that whereas the program was helpful immediately following the Jan. 12 earthquake, today it is having a perverse effect because people use their money mostly to buy imported food, or items – again, mostly imported – to hawk on the street.

Over half of the food Haitians eat is imported. In 2008, Haiti imported almost $1 billion in goods and services from the U.S. alone, spending some $325 million on food.

“We need the money to circulate in Haiti, not leave Haiti to go to another country. The money needs to stay in Haiti so that it will create work,” Chéry said, adding that to be useful, job programs need to be tied into a vertically integrated economic effort.

Another problem is that in the countryside, the programs – which are supposedly targeting earthquake refugees – appear to be drawing peasants off the land.

Agronomist Philippe Céloi, who supervises a six-month Catholic Relief Services program in the south, admitted that most of his 468 workers were local peasants, not refugees from the capital.

“After six months there will be benefits – not only the workers have gotten a salary but also the community benefits,” Céloi said.

Asked about farmers’ fields however, Céloi admitted there was a downside.

“These people are not doing the planting they ought to be doing. Right now it’s bean season… And they aren’t planting potatoes or manioc or sorghum, so when this program ends, there is going to be a problem,” he said.

But there is another impact that has become increasingly troubling to observers and even some implementers.

The American Refugee Committee recently had about 1,500 people a day working at camps in the capital.

“We helped people get immediate cash, as well as to help them get some things done within neighbourhoods and communities,” said Deb Ingersoll, ARC Cash-for-Work Coordinator.

But like economist Chéry, Ingersoll thinks it is time for the programs to stop, and she has another concern.

“I worry that we’re creating maybe a bad work ethic because I think that you see a lot of cash-for-work teams all over the city and the country and if you watch, those work teams aren’t necessarily… working,” she noted. “I worry that we’re providing… a visual association of working with not necessarily working hard.”

And this is only part of the negative effect the programs seem to be having.

Following the earthquake, in addition to providing much- needed emergency goods and services, humanitarian agencies spread out across Haiti, even into areas that weren’t really affected. Many have now set up shop in places like Les Cayes or Hinche, and now provide basic services, jobs and food.

Romel François, who used to be a street vendor and who now manages the cash-for-work teams at a camp in the capital, said he thinks the non-governmental organisations should take over Haiti.

“Our future lies with NGOs! We can’t count on the government. If it were for the government, we would be dead already,” he said.

In the countryside, Wilson Pierre, who heads the Perèy Peasant Association and is running a 600-job program, said that “whatever program that comes our way, we’ll do it. If it’s work, and we get paid, we’ll do it… I think these jobs should be permanent.”

These attitudes are “very concerning”, economist Camille Chalmers told Haiti Grassroots Watch. “This system of ‘humanitarian economy’ or ‘emergency economy’… is locking the country into a ‘humanitarian approach’ and a dependency on aid.”

And as people become more dependent, they become less engaged in their communities.

“There is a growing disconnect between what people think they can do as citizens because more and more roles are being played by NGOs and international actors in all domains… [and] it also legitimises the presence of international actors in all the domains,” Chalmers added.

“International actors” have been in Haiti for almost a century, and they have been active in both the economic and political spheres. [see Sidebar 2]

Chalmers and others are troubled to note that sometimes cash-for-work programs tie the two spheres together. A recent audit obtained by Haiti Grassrsoots Watch makes it clear.

The USAID Office of Transition Initiatives (OTI), which through Jun. 30 had spent over $20 million on cash-for-work programs, had as its primary goals to “support the Government of Haiti, promote stability, and decrease chances of unrest”.

In a letter attached to the audit, Robert Jenkins, acting director of USAID-Haiti and AID/OTI, reiterated that the primary goal was not rubble-removal, it was “stability”, and he added that the programs were “clearly branded as a Government of Haiti initiative”. In an election year, this heavily favours the incumbent party and its candidates.

Cash-for-work “is a double-edged sword, which doesn’t do anything for the country, and which can even cause damage,” said Adeline Augustin, a journalist from Radio Voice of the Peasant in Papaye and one of the Haiti Grassroots Watch journalists who carried out a three-week investigation into cash-for-work. “We need a sustainable economic plan based on national production.”

(SIDEBAR 1: What is “cash-for-work”?)

“Cash-for-work” (CFW) is a term used by humanitarian agencies to mean short- term unskilled labor jobs. A main objective is to get money circulating in order to “relaunch” an economy. The term appears to come from “Food for Work” (FFW), which humanitarian agencies have been using for decades.

In Haiti, CFW programs are aimed at earthquake victims who live in the 1,300 camps for displaced people or in the countryside with friends or family. A CFW job is typically eight hours a day, five days a week, for four weeks, with a daily salary of 200 gourdes (Haiti’s minimum wage, about $5). Typical jobs include: street- sweeping, cleaning drainage canals, rubble removal, repairing rural dirt roads by hand, and digging contour canals on hillsides.

Unfortunately for the Haitian government, for economists and for the public at large, no one person or agency actually knows how many people are working in the multitude of CFW and FFW programs in Haiti at the moment.

Origin of cash-for-work

While the term “cash-for- work” is a relatively recent addition to the humanitarian lexicon, the concept has been around for a long time.

British Economist John Maynard Keynes (1883- 1946) might be considered the father of “cash-for-work” because of his theory that the state must intervene in capitalist economies to lessen “booms” and “busts” and to create demand when needed.

During the Great Depression in the U.S., the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration put Keynes’ theory to work with New Deal jobs programs like the Work Projects Administration (WPA) which employed millions at a time.

But, as Robert Scheer recently wrote in his new book, ‘The Great American Stickup: How Reagan Republicans and Clinton Democrats Enriched Wall Street While Mugging Main Street’, capitalism is haunted by more than depressions and recessions:

“The great and terrible irony of capitalism is that if left unfettered, it inexorably engineers its own demise, through either revolution or economic collapse.”

FDR’s New Deal offers a perfect example. With thousands of jobless men and women marching on Washington, and with labor organisations and socialist or communist parties gaining strength, the jobs programs were likely as much about preventing revolution as they were about jump-starting the economy.

(SIDEBAR 2: Cash-for-work’s predecessors in Haiti)

For almost 100 years the U.S. and others have been overseeing jobs programs aimed at preventing “economic collapse” as well as “revolution” in Haiti.

In addition to using his “Tonton macoutes” terror squads, François “Papa Doc” Duvalier had a program of “make- work” jobs to help prevent any kind of uprising.

But long before that, the U.S. began what has turned out to be a series of radical interventions in the Haitian economy. The first one occurred during the U.S. occupation (1915-1934). By its end, over a dozen agro- industries had sat on hundreds of thousands of acres of land, offering the now-landless peasants jobs for 10 to 30 cents a day.

After the occupation, the U.S. government’s Ex-Im Bank backed mostly U.S. investors who set up companies that had New Deal-like promises of employing thousands and stimulating consumption. The programs and projects did produce many results, including corruption, deforestation, profits for foreign companies and debt – $33 million – for the Haitian government. But no real increase in jobs and demand.

In 1993, during the coup d’état, when Washington realised that the return of then-exiled President Jean-Bertrand Aristide was inevitable, USAID created an $18 million jobs program to “increase the income of many poor Haitian families” and “create a sense of confidence and hope”.

Focusing on rehabilitation and improvement of agricultural land, the “JOBS Initiative” was bumped up to a total of $38 million, running for 34 months, and reportedly employed 50,000 workers a day at its peak.

But a 1997 study, ‘Feeding Dependency, Starving Democracy: USAID Policies in Haiti’, showed that the JOBS Initiative produced few lasting results, since canals soon silted in and dirt roads reverted to their rocky state.

Instead, the program “actively strengthened anti- democratic forces and weakened grassroots, democratic organizations,” in part by providing jobs to supporters of the illegal coup regime. The report also said the program pulled peasants off the land, created new, “unsustainable” habits of consumption, hindered “volunteerism and community spirit and “generate[d] dependency.”

Was the objective really to “create a sense of confidence and hope”?

Or was it also to assure that supporters of Aristide and the progressive democratic and popular movement didn’t find terrain to mobilise once Constitutional order was restored in 1994? (IPS/GIN)