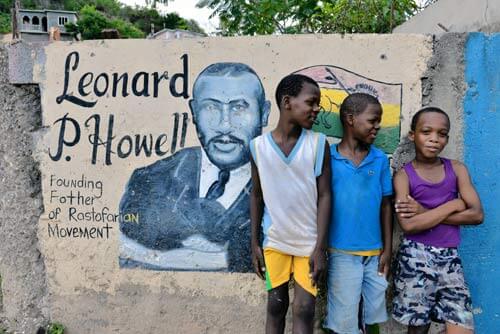

The month of February accommodates the celebration of Black History and Reggae Month. At times, much about the celebrations accentuates the outcomes at the expense of the process. For example, it is important to examine also the role of the black spiritual movements, their emergence and contribution to liberation. Leonard P. Howell’s contribution to anti-colonial politics in Jamaica, and indeed to the world, deserves recognition and honor.

In any other country Howell would have accorded heroic type status. His encounters in St. Thomas provide a rich account of his critical interventions that led to his arrest, trial and imprisonment. From these undertakings and events, a systematic explanation of his doctrine and its origin can be discerned. His observations, activities and interactions with those main characters assisted in the development of his anti-colonial and anti-imperialist political qualities. His colossal contribution to the anti-colonial struggles of 1938 gave rise to major influence to thought construction, culture, industry and self-reliance. Rastafari is a Jamaican phenomenon.

Some major misconceptions

The following sets out to dispel some major misconceptions about the origins and development of the idea and movement of Rastafari. There is an established view that Garvey was the prophet/philosopher of the new doctrine; and from the pluralist interpretation, four men started the movement simultaneously. Of course no evidence was given to support these charges. The evidence shows is that Howell was the founder/philosopher of the idea and movement. The proof shows that men like Hibbert and Hinds were followers of Howell. The confusion regarding Garvey was originated from interviews given to researchers by a certain group of Rastas in Western Kingston. There is a thinking that the idea and movement surfaced out of unemployment, structure in the slum and violent. In fact, Children of Sisyphus describes members of the Rastafari movement as ‘creatures of Dungle.’ The proof shows that the origins of the idea and movement began out of considerations more complex that the single story of unemployment. The verification shows that it was in St. Thomas that Howell was a successful preacher among labourers in the cane and banana fields and also among wharf labourers. The verification confirms that there is no evidence to declare that Howell was violent or racist person.

Howell was a prophet of the word, not the sword. There are those who interpret any form of black resistance against white superiority as racist. For example, there is a current primary school text, Religious Education: Work Book 5, written by C. Campbell and M. Miles (n.d. self-published) portrays Howell, the founder of the movement and also followers of Rastafari as preaching racism, hatred and violence. The book in misleading and must be pulled immediately from the school system. It maligns both the character to the man and the movement.

The unfolding of the history of ideas on the evolution of black Christian tradition and black spiritual movements illustrates their service to black liberation. There is a view that the thinking of Rastafari emerged from the history of the Myal and Revivalist tradition in Jamaica. Another outlook argues that the movement arose out of the history of the Native Baptist movement and its history of liberation struggles in Jamaica. There is also this extraordinary opinion that Rastafari emerged, ‘avowedly African,’ out of the Pentecostal led ‘Creole milieu’ of the 1830s. In his examination of Howell’s immigrant experience there is an implication by Robert Hill, 1981 in Dread History that the Prophet of Rastafari may have been influenced by Athyli Roger Hamatic Movement that appeared in the New Jersey / New York areas in the early years of the 20th century. This was close, but the evidence shows that Howell may have been influenced by the Father Hurley-led Ethiopian spiritual movement that began in the 1920s in the United States of America. He brought home to Jamaica December 1932 his core ideas on Rastafari.

Howell encounters in St. Thomas

Howell immersed himself into the operational environment – the rigid plantation society-in which he uttered fierce denunciations against the colonial society: the Church, the planters and the colonial authority (the police). Reports from the police, the planters and clergy men became part of the conspiracy that led to Howell’s arrest. Themes extracted from the encounters disclose his anti-colonial and anti-imperialist political qualities. The March 1934 of Howell was a political milestone in his anti-colonial journey. The new Ethiopian doctrine that appeared from his encounters was described by some sociologists and Marxists in terms of false consciousness, millennial bliss and fantasy, having no transformative or revolutionary qualities. They charged that it played no role in the anti-colonial struggles of the 1930s. The black spiritual existed long before the emergence of sociology and Marxism having a remarkable history in the service to black liberation. The verification shows that “the idea of black consciousness (of) the Rastas helped to instill confidence necessary to confront the British State.”

The Rastafari influenced strike and protest that resulted in a moment of resistance-clash with police- on January 6, 1938. It is important to note that prior to the clash with the police there was a meeting at the factory with Mr. Ehrenstein, planter and factory owner, and Mr. Bustamante, labour leader representing the planter. The labourers rejected the offer made by the planter; shouts of “traitor” were hurled against the labour leader. Both men had to be escorted to their cars by the police. The event at Serge Island was an illustration of the separation of the led from the leadership, making it a most important milestone leading up to the climax of the struggles of 1938. Against this background, the “Rastafarian millenarian ideology functioned as an active catalyst in the developing of the popular consciousness that led to the labour uprisings of 1938.”

Theology and Prophet

Rastafari thinking became the pinnacle in the evolution of black theology. It went beyond the idea of the separated black Christian movement of a new religion, having a new King and messiah. Howell demonstrated that man create God in his own likeness. He presented himself, as a messenger, a teacher and a man of prophetic proportion. Who is a prophet? The Machiavellian approach suggests that the periods of great instabilities in history are usually associated with the rise of individuals of prophetic qualities: they assert the will to lead; create their own political authority in advancing the politics of audacity that challenges the established authority. The 1930s was a period of extreme hardship, white supremacy/racist domination; and the planter control of the economic, political and social life of the setting’; and repressive manifestations of the Crown Colony government in Jamaica. Howell’s prophecy and its manifestations were associated with the command of and the assertion of authoritative images, metaphors and symbols that were proclaimed to challenge the established authority. His personal influence on the individual’s awareness and commitment of religion was amazing.

Philosophy and thought construction

Philosophy has to do with the treatment of complex issues, for example, matters concerning the emergence of Rastafari in the era of decolonisation. Howell, as an organic thinker, is important because he challenged the very foundations of Western thinking especially in religion, morality and perception of the self. The content of his thinking examines questions of the past and present; as well as universal issues such as human rights, the nature of god and religion, politics, ethics and values of self that inspired new cultural forms. In a practical way, Howell’s new doctrine was a radical critique that challenged the domination of white superiority, black inferiority and the oppressive system of European domination. It served as a medium in the debriefing process of the ex-slaves. His affirmation of the politics of redemption stirred the souls of ex-slaves towards new identity and liberation. Howell challenged the foundation of western civilisation-political thinking and religion- by advancing new ideas in morality and justice.

There is a view in Caribbean thought construction that the idea of the Rastafari doctrine contributed to the era of cultural nationalism in Jamaica. The new doctrine and nationalist thinking was the conception of a new moral order, as well as, fierce denunciation of Babylon from the early Rastafarians created “an abyss between the master and classes.” Another opinion suggests that, rooted in the history of the black protest movement, the idea of the early Rastafari is a “coherent system of belief;” and that the Hegelian idealist tradition is effective in trying to make sense of this new doctrine characterised by spirituality, morality and the fatherland. There is a view that the subversive practices of Rastafari is characterised by philosophical qualities rooted in Christian moral tradition, African belief and Hegelian idealism. The new doctrine inspired novel formations in literature, popular culture among others. There is that fascinated history of the link of Rastafari, celebratory activities at Pinnacle and the root of Reggae music. The work of Barry Chevannes on Pinnacle, Reggae and Rastafari inspired cultural studies researchers, such as Yoshiko Shibata Nagashima, 1976 and Bilby and Leib, 1986, to explore and to examine the evolution of Reggae music from Pinnacle to western St. Andrew and western Kingston. During the 1970s Reggae music became a new platform from which the good news was spread across the world. Roger Mais in The Hills Were Joyful Together, Brother Man, Black Lightning; Andrew Salkey’s The Late Emancipation of Jerry Stover and Orlando Patterson in Children Of Sisyphus, to name a few. In the context of the concrete, Pinnacle was an industrial mission fostering industry and self-reliance.

Some recommendations

This article calls for the state to initiate its investigation into the history of the 1930s with a view to honour Leonard P. Howell for his contribution to politics, culture, thought construction, industry and self-reliance in Jamaica. The Rastafari Movement is a global phenomenon and its founder is hardly known. Official recognition is necessary to elevate Howell’s name to its rightful place in Jamaica’s history. By any measure and definition, he was a man of heroic proportions. The article also offers a clear guide to the emergence of the idea and movement with the aim to inspire further studies relating to the philosophical and theological qualities of the movement. It calls on the young Rastas to explore the history, to seek deeper insights into possibilities leading to outcomes for new development of: rites of passage for the young; rites for birth marriages; rites for death/burial. There is also the need to recapture the foundational ideas of the movement with a view to develop of policies and programmes to reinvigorate the ideals of self-reliance and industry building among the growing Rastafarian Movement in Jamaica and the world. The war against Rastafari in Jamaica did not stop the expansions of the movement, but it may have contributed to the stifling of its development. In spite of the retardation of the Rastafari movement it remains a potent political force in 21st century Jamaica. What began as an obscure rural movement flourished into the largest black consciousness movement in the world.