The remarkable overlooked story of more than 2,000 African-Caribbean soldiers imprisoned in a medieval castle in the 18th century is to be told in a new exhibition by English Heritage, according to reports.

It comes after more than five years of painstaking research into the men — and 99 women and children — who were transported from St. Lucia in 1796 to Portchester Castle, which overlooks Portsmouth harbor, a large natural harbor in Hampshire, England, reported the British Guardian on Tuesday.

The paper said the prisoners of war (PoWs) were all black soldiers and their dependents, freed from slavery by the French in 1794 and fighting for France against the British.

Among the names, the Guardian said, were Louis Delgrès, General Marinier and his wife Eulalie Piemont and Charlotte Pedre and her husband Jean-Louis Marin.

Curator Abigail Coppins said that discovering individual identities had been astonishing.

“At a time when the entire black population of Britain was roughly 10-15,000, our exhibition completely turns the tables of the views of the period,” she told the Guardian.

“These were not slaves, but free men and women, fighting and, in some cases, dying for a cause they believed in,” she added. “Research is on-going, but these names and this exhibition restores a forgotten chapter of black history in England’s story.”

The story of the prisoners of war is fascinating and little-known, said the Guardian, adding that, after the French Revolution, slavery had been brought to an end on the islands of Guadeloupe, St. Lucia and St. Vincent and the Grenadines, and many of those families joined the fight against the British.

In 1796, Fort Charlotte, a fort on St. Lucia, surrendered to the British, which meant more than 2,000 African-Caribbean soldiers and their families came into their care, the Guardian said.

It said that, as was the convention of the time, they were treated as prisoners of war to potentially be traded in exchange for British PoWs.

They were brought across the Atlantic in a convoy of ships, arriving on the Solent as winter began setting in, said the Guardian, adding that it would have been a complete culture shock.

If the contrasting weather and diet were not bad enough, the Guardian said they were also bullied by European prisoners already being detained in the castle.

Coppins said there were attempts at compassion with, for example, the prison doctor insisting on the prisoners being fed more potatoes because it was the nearest he could think of to yams, according to the Guardian.

At some point, the prisoners were moved from the castle to two brand new prison hulks, Captivity and Vigilant, moored close by.

By the end of 1797, the Guardian said most of the PoWs appear to have been dispersed, with some going on to form part of a battalion of black pioneers which saw action in France, Italy and Russia. Some even ended up fighting for the British navy.

Coppins, according to the Guardian, first came across the story by accident.

“It was a long cold winter, and I’d been repacking the archeological files from the castle and I’d had enough of Roman animal bones,” she said.

She said she turned her attention to the Napoleonic period, when the castle was used as a detention center for prisoners of war.

“What little I did find out stopped me in my tracks,” Coppins said. “I just hadn’t realized how many different nationalities were imprisoned or interned at the castle.”

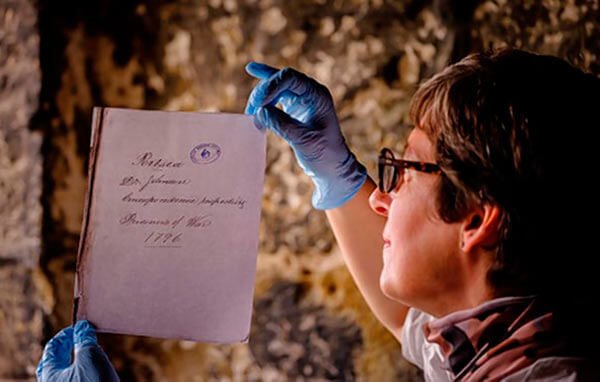

Sifting through archives, Coppins has managed to put names to people who have fallen through the gaps of history, said the Guardian, adding that the most famous of the names she has discovered is Captain Louis Delgrès, who later became leader of the resistance movement in Guadeloupe, fighting the reinstatement of slavery by Napoleon.

He and his followers died in horrible circumstances in 1802, the Guardian said.

Facing defeat, it said Delgrès ignited his gunpowder stores knowing that they all would be killed, but it would also kill many French soldiers.

Coppins said discovering the identities was an important exercise.

“It is almost impossible to find images of the soldiers,” she said. But, by giving them names, you give them their place in history and their relevance.”

The exhibition at Portchester Castle opens on Thursday, the Guardian said.